Obama advisors raised warning flags before Solyndra bankruptcy

Treasury chief Timothy F. Geithner and others were worried that the selection process for federal loan guarantees fell short and raised the risk that funds could be going to the wrong firms.

By Tom Hamburger, Kim Geiger and Matea Gold, Washington Bureau

6:35 PM PDT, September 26, 2011

Reporting from Washington

Advertisement

Long before the politically connected California solar firm Solyndra went bankrupt, President Obama was warned by his top economic advisors about the financial and political risks of the Energy Department loan guarantee program that boosted the company's rapid ascent.

At a White House meeting in late October, Lawrence H. Summers, then director of the National Economic Council, and Timothy F. Geithner, the Treasury secretary, expressed concerns that the selection process for federal loan guarantees wasn't rigorous enough and raised the risk that funds could be going to the wrong companies, including ones that didn't need the help.

Energy Secretary Steven Chu, also at the meeting, had a different view. Under pressure from Congress to speed up the loans, he wanted less scrutiny from the Treasury Department and the Office of Management and Budget, or OMB.

The divisions foreshadowed a question that has emerged since Solyndra's bankruptcy: Was the program's vetting process thorough enough? The disagreements also spotlighted an issue that has confronted Obama since he took office: What is the appropriate role of the government in stimulating the private marketplace?

Skeptics, noting that taxpayers could now be on the hook for $527 million the federal government loaned Solyndra, said the administration would have been better off making greater use of market incentives, not individual company loan guarantees.

"It was completely predictable that there would be a colossal failure among the bets," said one person familiar with the internal debate.

Defending the program as an overall success, administration officials say that the $17 billion in loan guarantees now on track to go to 30 companies will help double renewable energy generation in Obama's first term.

The program that funded Solyndra is set to expire at the end of the month, and the White House is pushing to provide more green-energy loan guarantees through other initiatives and keep the U.S. competitive globally. The Chinese government, the Energy Department says, last year committed $30 billion to solar-panel manufacturers.

Almost immediately after the 2008 election, Obama advisors began debating how to create jobs while reducing the nation's reliance on fossil fuels. Some advisors pushed to expand a George W. Bush administration loan-guarantee initiative to help green-energy companies launch commercially. Others were philosophically opposed to providing help to individual companies and warned against betting taxpayer money on inherently risky ventures.

Nevertheless, the administration went forward with the loan guarantee program as part of the 2009 stimulus law. High-level disagreements on the program continued.

In late October 2010, administration officials took their opposing views directly to Obama. In preparation, a memo was drafted by Summers, who remained wary of the program, and two others who were more supportive: then-energy advisor Carol Browner and Ron Klain, then chief of staff to Vice President Joseph Biden. The memo laid out their different concerns and options to fix a "broken process" for getting loans approved.

Warning that the program could "fail to advance your clean-energy agenda" by investing in companies that didn't need help, the memo proposed alternatives, including diverting the funds into grants available to the entire industry. By contrast, Energy Department officials wanted to end the "deal by deal" reviews by the Treasury and OMB, the memo said.

After the meeting, officials worked to streamline the process but didn't make significant changes.

It is unclear whether an overhaul would have helped anticipate the problems at Solyndra. In February, the Energy Department agreed to restructure the company's loan. A little more than six months later, Solyndra declared bankruptcy, laying off 1,100 people and triggering FBI and congressional investigations.

The administration originally touted the green energy program as a tool that would create or save tens of thousands of jobs. So far, 30 projects are on track to create about 16,750 construction jobs and 2,577 permanent jobs. The Energy Department notes that a related loan guarantee program helped save 33,000 jobs at Ford by helping the company modernize its factories.

But some critics argue that other government loan guarantee programs do a better job of protecting taxpayers.

For example, a Transportation Department program to spur infrastructure improvements limits loan guarantees to 33% of the cost of a project, said Autumn Hanna of the nonpartisan Taxpayers for Common Sense. Energy Department guarantees can amount to 80%.

Critics also question whether the Energy Department has the expertise to select which companies to help.

"Questions have to be raised about the quality of their analysis," said analyst Shyam Mehta of GTM Research in Cambridge, Mass.

Jim Nelson, chief executive of Solar 3D, a Santa Barbara company that is developing three-dimensional solar cell technology aimed at making more efficient solar cells, said the government should stay out of the business.

"If private investment cannot find a reason to invest in emerging technology to make it commercial," he said, "what is government doing it for?"

Energy Department officials counter that only projects that have met the test of the marketplace are considered.

"We don't pick winners and losers," spokesman Damien LaVera said. "The private sector does." Companies selected for loan guarantees, he added, have been "deeply, deeply, deeply capitalized by the private capital markets."

Many clean-energy investors say the loan guarantees have been essential to getting capital flowing, particularly during the credit crunch. It's important for the government "to bridge this difficult gap between where venture capital is able to fund these companies and where traditional project finance kicks in," said Sunil Paul, a San Francisco-based clean-energy investor.

Rhone Resch, president and chief executive officer at the Solar Energy Industries Assn., credited the program with creating "more than $40 billion of private investment in both energy generation and manufacturing projects," and said the solar projects selected would not have gone forward without government backing.

But government audits in recent years have found problems in the implementation of the program.

A July 2010 report by the Government Accountability Office found that the department committed to back the loans without completing required studies of market, legal and technical issues.

"Without this information, it is not clear that the program could have fully evaluated the risk of the loans it committed to," said Frank Rusco, an analyst for the GAO.

tom.hamburger@latimes.com

kim.geiger@latimes.com

matea.gold@latimes.com

Melanie Mason in the Washington bureau contributed to this report.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

And tell your friends too!!!

Obama was an Alinsky trainer at ACORN

WRD began in January 2010 at the height of the Obamacare debacle. Since then, WRD banded with a group of like-minded individuals to form the Gadsden Group, influencing thought by challenging bias at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, volunteering for Republican candidates, participating in numerous campaign events, networking with other groups of concerned citizens, and gaining a foothold in social media on Twitter. Our "Letter to to the Left" after Governor Walker's convincing win in the June 2012 recall election went viral, and we decided to officially expand this site to include the Gadsden Group name.

We hope this site will be a one-stop shop for great websites, articles, polls, conservative commentary, and more. 2010 was the year of the Republican comeback, and 2012 was off to a great start with the convincing win of Scott Walker, but we have much work to do after the Romney and Thompson defeats, and it's up to all of us to make it happen. Share with friends, convince your kids, do your part to get our great country back! Thanks for visiting our site! Wisconsin Republican Dad and everyone in the Gadsden Group

"I also am a total loser"

3 victories in 4 year, this is uncharted water. Take that you lefties!!!!

wish I had thought of this one!

Send your donation to the Trotsky/Alinsky Center for the Insane

Thanks NSA!

Yuck!

One of the worst things I've ever seen on social media, and that's saying something. Disgusting.

What's the penalty for treason again?

"I go skeetshooting all the time" LOL

Benghazi-Gate is the end of O's political career whether he wins re-election or not. Let's make it not.

"Thanks for ruining our 20th anniversary meanie!"

Dear Leader violates the Flag Code. He should be arrested for putting his image on the flag while being a sitting POTUS. People have died for our Flag. These $35 flags from obama.com are a National disgrace.

Try putting this one on your Dane County SUV!!!

Those guys are working overtime over there

What kind of a vile, despicable person drives this car? (A Hyundai in Detroit as well)

This Massachusetts billboard gets it right!

Thank you Clint Eastwood for the Empty Chair!!! Great stuff!

The day the people were forced to take back their country

Romney for 8, Ryan for 8, Walker for 8, Rubio for 8. Then we die old & happy.

The Wisconsin Boys welcome the next POTUS to WI, the state that saved a country!

What could possibly get between you and your doctor?

Your kids all thank you!

The 1770's flag has made a huge comeback, and for good reason...

"he even writes lefty"

Another great campaign slogan: "Transparency!"

Those marketing folks are working overtime over there...

Please stay in the right lane...

Don't let the Takers defeat the Makers: Defeat Obummer in 2012

I'm kinda diggin' the new slogan: transparency finally?

The Democracy will ceast to exist when you take away from those who are willing to work and give to those who would not.

--Thomas Jefferson

"available at fine clothiers and wherever English is Spoken"

"Republicans believe every day is the 4th of July, Democrats believe every day is April 15th."

Close your eyes...breathe deeply...imagine...

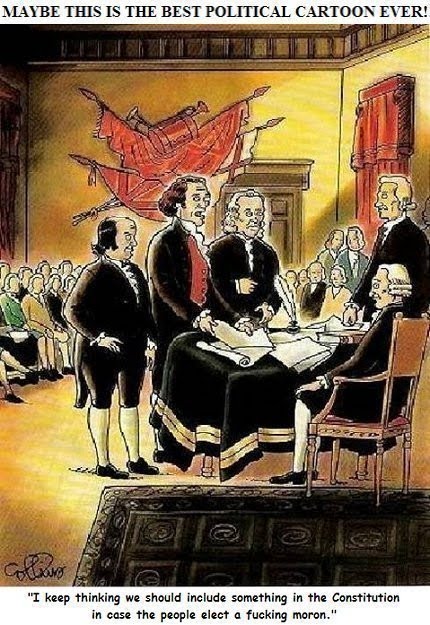

"Thomas, I really think we ought to include this???"

"or what lefties refer to as, those pesky little first 10 amendments that prevent us from stomping on the great unwashed"

Ronaldus Magnus, on a billboard in the Twin Cities

Media Trackers

MacIver Institute

Wisconsin Republican Dad's favorite links

- Breitbart

- American Thinker

- Americans For Prosperity

- Bernie Goldberg

- Bill O'Reilly

- Citizens for Responsible Government

- Dick Morris

- Drudge Report

- Fox News

- Freedom Works

- Grandsons of Liberty (WI)

- Heritage Foundation

- Hot Air

- Learn the Truth About Obama's Past

- Mark Belling

- Mark Levin

- Michelle Malkin

- Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

- National Review

- Paul Ryan

- Politico

- Real Clear Politics

- Red State

- Right Wisconsin

- Ron Johnson

- Scott Walker

- The Daily Caller

- Track liberal bias at the New York Times

- USA Today

- Vicki McKenna

- WISN Common Sense Central

- Where the lefties hang out

- Young America's Foundation

Follow us on Twitter @Gadsden_Group

And tell your friends too!!!

If you understand Alinsky, you understand Leftists

Obama was an Alinsky trainer at ACORN

Welcome to our blog!

WRD began in January 2010 at the height of the Obamacare debacle. Since then, WRD banded with a group of like-minded individuals to form the Gadsden Group, influencing thought by challenging bias at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, volunteering for Republican candidates, participating in numerous campaign events, networking with other groups of concerned citizens, and gaining a foothold in social media on Twitter. Our "Letter to to the Left" after Governor Walker's convincing win in the June 2012 recall election went viral, and we decided to officially expand this site to include the Gadsden Group name.

We hope this site will be a one-stop shop for great websites, articles, polls, conservative commentary, and more. 2010 was the year of the Republican comeback, and 2012 was off to a great start with the convincing win of Scott Walker, but we have much work to do after the Romney and Thompson defeats, and it's up to all of us to make it happen. Share with friends, convince your kids, do your part to get our great country back! Thanks for visiting our site! Wisconsin Republican Dad and everyone in the Gadsden Group

Total Pageviews

Blog Archive

About Us

- Wisconsin Republican Dad

- WRD: I'm just a dad and husband who's very worried about the direction this country is going, and decided it was time I got involved. I believe in fiscal restraint, personal responsibility, a much smaller goverment, fewer government programs, agencies, and entitlements, strong national defense, and justice for criminals. I want our borders strengthened, tort reform, a balanced budget, and deficit reduction. I believe in Constructionist judges, not liberals who legislate from the bench. I'm pro gun, I'm for expanding nuclear power and offshore drilling. By default, that makes me a conservative Republican. The liberals are killing this country, and worse, they know it. Their desire to be liked, to be seen as champions of the poor, while they continue to grow the welfare state, bothers me greatly. Because arrogance is the worst of human traits, their condescension (that means you Russ Feingold) towards middle America makes me want to scream. So I am... Gadsden Group: We are a group of like-minded individuals based in Waukesha and Milwaukee counties (WI). We're sick of liberals running our state into the ground, so we decided to make a stand. So far, so good...

Very, very true...

Liberal tears....

"I also am a total loser"

We won! Again!!!

3 victories in 4 year, this is uncharted water. Take that you lefties!!!!

This says it all perfectly

wish I had thought of this one!

Leftists...

Differences

Please, can you help us find a cure?

Send your donation to the Trotsky/Alinsky Center for the Insane

The official definition of liberal

Obama's Desktop

Thanks NSA!

Sounds about right...

Sounds about Right

Please, no more desecration of the White House from these Hippies

Yuck!

Perhaps the best t-shirt evah!

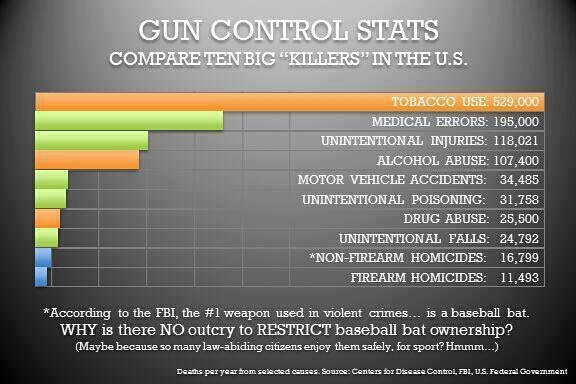

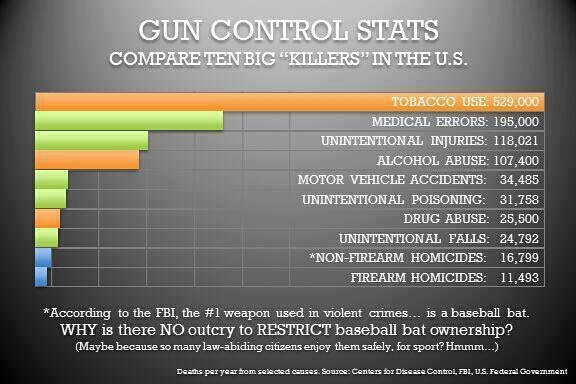

2A

Here's one man who can save our counrty

That liberal lion, John F. Kennedy

Welcome to Wisconsin

The sick freak polymath22 posted this fake image of murdered Martin Richard

One of the worst things I've ever seen on social media, and that's saying something. Disgusting.

TRAITORS! TREASON!!!

What's the penalty for treason again?

What we're up against, #5,678,890

Our Idiot in Chief using his Prompter

"I go skeetshooting all the time" LOL

"What Difference Does it Make?"

Ronald Reagan (deceased) summarizes the Newtown killings

"We must reject the idea that every time a law's broken, society is guilty rather than the lawbreaker." -

--Ronald Reagan

--Ronald Reagan

And it begins...God Help us

Watching Americans die in Benghazi, and not assisting, leads to:

What have we done...

Oct. 25th, 2012 cover, New York Post

Benghazi-Gate is the end of O's political career whether he wins re-election or not. Let's make it not.

Words spoken were never truer...and he said them!!!

If looks could kill...

"Thanks for ruining our 20th anniversary meanie!"

DEFICIT!

Obamanation

This flag desecrator must be stopped NOW!!!

Dear Leader violates the Flag Code. He should be arrested for putting his image on the flag while being a sitting POTUS. People have died for our Flag. These $35 flags from obama.com are a National disgrace.

Now that's funny!

Try putting this one on your Dane County SUV!!!

The New Obama Slogan

Those guys are working overtime over there

My buddy Al G. from near Detroit took this photo...

What kind of a vile, despicable person drives this car? (A Hyundai in Detroit as well)

Thank goodness we're all computer-savvy!

This Massachusetts billboard gets it right!

The best empty chair photo I've seen so far!

Thank you Clint Eastwood for the Empty Chair!!! Great stuff!

June 28, 2012

The day the people were forced to take back their country

I don't care who you are, that's funny!

The great Paul Ryan

Romney for 8, Ryan for 8, Walker for 8, Rubio for 8. Then we die old & happy.

This is perfect for Andrea Mitchell, since she already is a dog!

June 18, 2012

The Wisconsin Boys welcome the next POTUS to WI, the state that saved a country!

Obamacare

What could possibly get between you and your doctor?

Quote that pretty much says it all

"As an American, I am not so shocked that Obama was given the Nobel Peace Prize without any accomplishments to his name, but that America gave him the White House based on the same credentials." --Newt Gingrich

Congratulations to all the 54% ers!

Your kids all thank you!

Got it Leftists? Understand? I didn't think so...

The 1770's flag has made a huge comeback, and for good reason...

"Here's to hoping this isn't your kids' teacher"

Obama's New Bill of Rights

"he even writes lefty"

Obama Marketing team is hard at it!

Another great campaign slogan: "Transparency!"

New campaign slogan for the Obummer juggernaut

Those marketing folks are working overtime over there...

Let's drive a little more carefully this time, OK?

Please stay in the right lane...

Don't let the Takers defeat the Makers: Defeat Obummer in 2012

I'm kinda diggin' the new slogan: transparency finally?

Thomas Jefferson, not exactly a fan of the welfare (ie. liberal) state

The Democracy will ceast to exist when you take away from those who are willing to work and give to those who would not.

--Thomas Jefferson

Scott Walker's Phone # if needed

Governor Walker's office # is 608-266-1212. Please feel free to call him and thank him for everything he has done, if you have questions, anything at all. This is what transparency looks like!!!!

Dads Against Daughters Dating Democrats

"available at fine clothiers and wherever English is Spoken"

Ronald Reagan

"Republicans believe every day is the 4th of July, Democrats believe every day is April 15th."

www.thoseshirts.com

Close your eyes...breathe deeply...imagine...

A clause that didn't make the final draft

"Thomas, I really think we ought to include this???"

The Bill of Rights

"or what lefties refer to as, those pesky little first 10 amendments that prevent us from stomping on the great unwashed"

I wonder what he's thinking now???

Ronaldus Magnus, on a billboard in the Twin Cities